Episode published: Friday 01/31/2025

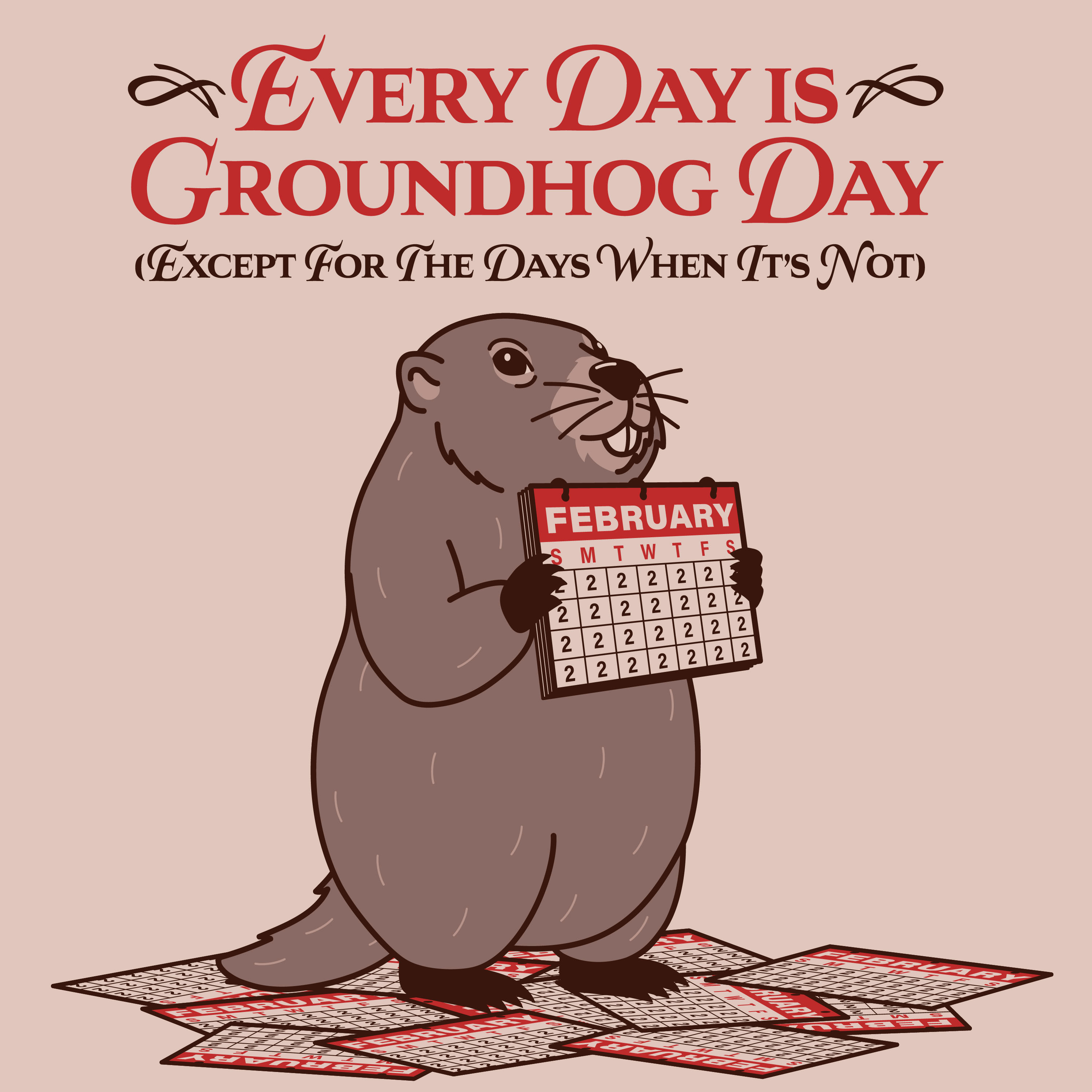

Michael: Hi gang, welcome to another episode of Every Day is Groundhog Day (Except for the Days When It's Not), the only podcast about the best holiday there is. I'm Michael from countdowntogroundhogday.com, and I'm your host.

For today's episode, we have something really exciting. A few weeks ago, I was fortunate enough to speak with the original screenwriter of Groundhog Day, Danny Rubin. We got to talk about how he came up with the idea for Groundhog Day, working with director Harold Ramis and Bill Murray, how the idea for the Groundhog Day musical came about, and much, much more. Because this is a long interview, we're going to release it in two parts. One today, and one on Sunday as a special Groundhog Day treat. Hope you enjoy! Here's Part One of the interview with Danny Rubin.

Michael: Today, I'm here talking with Danny Rubin, writer of not just the movie Groundhog Day, but the Groundhog Day musical as well. So welcome, Danny, to the podcast. It's a real honor.

Danny Rubin: Thanks, Michael. Thank you.

Michael: So, obviously, I'm a big fan of the movie, and we'll get to Groundhog Day soon enough. But I was wondering if you could give a little background on yourself, you know, at what point you decided to be a writer and generally, what you were doing before starting to write Groundhog Day.

Danny Rubin: All right. I was raised in Gainesville, Florida in the age of science and reason, and my dad was a doctor. So, I was sort of into the world of science, and I was pursuing biology in college, but mostly because I had enough credits already that I got a good jumpstart, and it didn't have too many distribution requirements. What I really wanted was just a general education. For some reason, growing up in Gainesville, Florida, I felt a little less educated than I could have been and I thought, "Well, let me just take some classes that I've never taken before and learn something." And I was slowly getting drawn into the media as just being more to my interest and some level of production and entertainment.

I wasn't even sure where or how, but I started doing little media-related jobs after college and at some point, I got dragged back into graduate school at Northwestern in Radio, TV, Film. I was hoping to just take a year off of my young adult life and try and figure out what was going on in the industry. At the time, cable was just exploding on the scene, and I wanted to figure out where to position myself to take best advantage of this historical phenomenon. And I had applied after grad school to a public television station in Chicago, WTTW, that did a lot of production, and I saw myself as being in this, kind of, nexus between education and entertainment. That didn't work out, but the producer said, "Wow, this is a pretty well written application. Why don't you just be a writer?" I said okay, because I didn't have any better ideas and just started learning about industrial writing.

I was living in Chicago at the time, and I wrote for anybody who had an opportunity for a writer. I did comedy writing; I wrote a one act play that got me involved with The Practical Theatre Company in Chicago and the Wavelength Improv Institute, both of which made a little bit of money and got me exposed to an awful lot of very cool people. And at some point, somebody said, "Oh, why don't you write a movie?" And I said, okay. And I sat down and brainstormed a bunch of movies, one of which was Groundhog Day, by the way, but I wound up writing a different one, sent it out into the ether. somehow it got noticed and I wound up getting a job as a screenwriter. And that, to me, was like definitive and "Yes, I could do this. This sounds like fun. This seems like within my wheelhouse." And I'd finally gotten a foothold in something that was in the creative field, and I thought, "Go for it."

So, that's how I wound up becoming a writer, it was sort of by doing everything until that thing chose me. It seemed easier to get involved with writing than a lot of other roles within film just because you could do it alone. You didn't have to wait to organize a bunch of people to go put on a show or do a little production, some of which I did, you know, during the ‘80s when I was trying to figure out what I was doing. So, I'd done some production, I'd done some writing, I'd done some assisting, I'd worked in local children's television, I was a songwriter and was doing things at the Chicago School of Folk Music [laughs] and meeting other people and just waiting for something to choose me and it wound up being writing.

Michael: So, kind of a long circuitous path.

Danny Rubin: I guess. I just felt like I was bouncing around from this to that. It took me a good 10 years after college to stop getting science journals and things like that. I was afraid of letting go of all that knowledge that I had in case it came in handy. And it did in small ways, but not in needing to keep up with the journal kind of ways. So, I finally transformed from basically a left-brained person to a right-brained person over about 10 years.

Michael: So, I did want to mention, you did write a book called How to Write Groundhog Day back in 2012, which does cover a lot of the things we're going to be talking about today, I'm sure, and a lot more. So, I do want to recommend that everybody go and check that out if they have any questions that we don't answer here. One of the things you mentioned, I think you kind of alluded to just now, it seemed like you were considering maybe becoming a doctor or going into some sort of medical field, is that…?

Danny Rubin: It was a way to start walking in any direction. I didn't know what I wanted to do, and that seemed like a good enough place to start. It wasn't until, I don't know, I did some serious thinking about it, maybe two years into college, and kind of decided a couple things. One, that I probably wouldn't go to me as a doctor, [laughs] or about half the people I was in classes with, really. The other thing was sort of trying to figure out why I was attracted to medicine in the first place. There were a variety of noble reasons, but ultimately, I traced it back to having gone to a movie with my dad called The Interns that took place at a medical school. Somewhere during the course of this drama—none of which I can remember, actually—there were the students putting on a sketch comedy show that satirized the medical school and their professors, et cetera. And I realized I just wanted to be in that sketch comedy show, the rest of medical school was not of that much interest to me, but doing satirical comedy was very, very exciting for me. And I realized I could skip medical school altogether and just… [laughs]

Michael: Just do the comedy.

So, you mentioned industrial writing, could you talk about that a little bit? Is that just, like, commercials or films that are meant for a specific, like, how to use a product? Something like that?

Danny Rubin: Exactly. There were several multinational corporations headquartered in Chicago, and they all had in-house media departments. Sometimes they had their own film departments, and they would produce their own videos, and they would hire outside people to write them. Somewhere around there, this was the early 1980s, corporations were realizing that their employees, if you gave them a stack of things to read, "These are our practices, these are our policies," whatever, nobody read them, or they didn't absorb them. But if you hired some funny writers to make funny little videos about them, they would watch the videos. So, this was, I learned, how writers in Chicago made money while they were trying to develop their craft. And they did. I had friends who were children's playwrights and novelists and various kinds of writers who all were able to make money by, you'd make a film for McDonald's on how to shave seconds off your delivery time at the counter, or from Wickes Lumber, how to build a pole barn. I did one for Sears. They were just starting to fire salespeople and put little video monitors in the aisles instead to, sort of, promote their products and I wound up, actually, my very first industrial job was for Sears Tires, and I wrote a parody of Rear Window called "Rear Tire." So, it was a thriller starring a tire. [laughs]

Anyway, so these industrial films are a big way of writers being employed to do this and I knew writers who just sort of said, "Oh, I think I'll just do this, this is kind of fun," so they kept up that as part of their career. I was always just of the mind that I would rather be doing any kind of writing job than anything that was not a writing job. So, rather than working in a restaurant or something, I would take any writing job that came along so that included all the industrial writing. I was able to support myself while I was getting better and figuring out what I was up to.

Michael: Do any of those videos exist out there in the world? Anything on YouTube? What was the one from Sears? "Rear Tire"?

Danny Rubin: That was called "Rear Tire." I doubt it, I doubt it. This is from quite a long time ago. If I had any original tapes, they're on one-inch VH, you know, one-inch video.

Michael: You mentioned that there are a number of ideas when you— I think you said that in the book, there was like a screenwriting contest and you just mentioned you had come up with a number of ideas for that, like, 10 ideas that you would be willing to make in the screenplays. And there was the one, I think you called it Silencer, and it ultimately became Hear No Evil?

Danny Rubin: Mm-hm.

Michael: Okay. And that became a film that was, was that around, that was maybe, like, a year before Groundhog Day?

Danny Rubin: I had three movies that came out within a year of each other. So, I don't know the exact order of what happened, but it was in the mix. That was the first one that I sold as a spec script.

Michael: And how involved were you with that?

Danny Rubin: That was a situation where it was in development for a few years and I wrote many, many, many drafts. The issue, I think, at the heart of the difference between my approach and the director's approach was that it was, the seed was bad guys chasing Marlee Matlin, a thriller in the deaf community. And I saw that as a very Hitchcock-y thing like North by Northwest. They were quite taken with the idea that it was just like Wait Until Dark, which is bad guys chasing a blind woman, and I kept trying to explain to them that being blind and being deaf are very different and have different kind of tone, et cetera. But I could not disabuse them of what they were looking for, which I have learned after many years in development in Hollywood, is that's not what you do. You can figure out how to get everybody to "Yes," it's not about how they are ruining your movie. [laughs]

But I stuck to my guns and eventually they hired another writer, and then another writer, and then another writer. So, it wound up, I got a credit on it, but it was the smallest credit you could possibly get because it was still my project, but they had rewritten it so much that it just had some resemblance to what I'd originally written. So, I was not involved in the production of that.

Michael: So, do you still own any rights? I mean, we can get to the Groundhog Day musical later, but I saw that you had the theatrical rights for Groundhog Day.

Danny Rubin: I doubt it. I don't think I got enough credit on that to have enough rights. On Groundhog Day, I was the original writer and so that gave me a preponderance of weight in the rights department that allowed me to have that separated right to make a book of the screenplay, which I did, as you mentioned, and to do a musical.

Michael: One other question about those original ideas. You said the original screenplay you wrote was the Knee Biter Institute? Is that how you would pronounce that?

Danny Rubin: Yes.

Michael: And that seems like an interesting idea. I think you said it was a genius dies, and he donates his organs to science, and then the recipients can kind of combine to make up the original genius, but they all have to be, like, working together.

Danny Rubin: Yeah, you sold it pretty well there. It's a silly premise that maybe has some interesting societal and religious overtones, but ultimately it was like, well, it proved to me that I could write a screenplay, but it also in reflection, it was like, who's the audience for this? I was just writing it out of a creative idea, but I wasn't thinking at all about who would buy this, who would watch this, who would want this. It's a little bit too weird for kids and a little bit too silly and whimsical for adults. So, I didn't even try to send it out to sell it. I, at most, showed it to some friends and they said, "Wow, this is a real screenplay. You should do more of these." And I went, "Okay."

Michael: So, I think you called it Time Machine in the original and that that's what became Groundhog Day and Silencer. Have any of those other ideas become anything that was produced, or have you tried, or are they anything that you have considered working on? You probably aren't still trying to get Knee Biter Institute made. But I don't know, you know, you never know.

Danny Rubin: Right. I tend not to go back and try to resell old stuff just because Hollywood in general tends to think anything that's already been looked at once is tainted. So, you know, I've had agents take old scripts of mine and tell me to put a new title page on it with a new date just in case they hadn't read it. And that usually doesn't work, they usually have a vetting process where some underling checks to make sure it hasn't already been vetted in their files. So, no. I'm always a moving forward kind of guy anyway. I don't want to try and resell stuff.

That being said, I wrote something about 20 years ago that people keep trying to make. And once again, there's a little bit of a push to get it to happen, which would be nice because it was sort of a timeless idea, so it doesn't become dated very much. Out of those original ideas, there might have been a third one that I wrote that got some action, but I'm not even thinking clearly of which one that would be. But I haven't gone back to that list, really, I'm always coming up with new things.

Michael: That idea that you said might be getting some traction, is that something you can talk about? You got to keep that close held for now?

Danny Rubin: Oh no, I don't mind. I mean, it's been out there forever. The shortest way to describe it is as my Scheherazade Western. There's a guy being taken out to be hanged and they say, "Any last words before we hang you?" And he starts to tell the story pretty much of how he got into this situation. So, it's a story being told by a person with a noose around his neck and it keeps cutting to the story, and then cutting back to him. It's late and he doesn't want to talk anymore, and they say, "Well, maybe we can hang you tomorrow," because they want to hear what happens. Ultimately, they let him go because the story that he tells them teaches them compassion. So, it's a lovely story and it's just a matter of getting the right people together in the right exact adventure and the right tone. But I don't know if anyone wants to make it, I'd love to write it… again. [laughs]

Michael: All right. Well, I look forward to hopefully, hopefully it does get made and I'll keep an eye out to see if… Definitely let me know.

Danny Rubin: Don’t hold your breath. It's been a while. There were several times when it was an absolute sure thing.

Michael: So, could we talk a little bit about the writing of Groundhog Day?

Danny Rubin: Yeah, what do you want to know?

Michael: I know in the book you mentioned that you had considered some other ideas, some other holidays to possibly base the day around, that it would be set upon. Could you talk about that a little bit and, like, how you settled on Groundhog Day?

Danny Rubin: Sure. After coming up with this idea of a person repeating the same day over and over again, I had to figure out, well, who's the person and what is the day? How do I build this into a movie story? I had plenty of great ideas very quickly about what would be fun for that character and what kinds of scenes a person could see that would be interesting. But I couldn't even start writing that unless I knew, is it night? Is it day? Is it sunny? Is it cold? Is it in a big city? Is it in a small town? And I was just looking for a reason to choose one day over another day.

The first thing I did was just look at my calendar and basically the very first holiday I came to was about two or three days later was Groundhog Day. And I thought, "Oh! That's a great idea." It's a great idea because everybody's heard of it, but it doesn't really have anything associated with it, it's just a ridiculous holiday that means nothing. And I happened to know from an industrial job I'd had for Bell of Pennsylvania that there was a town called Punxsutawney where this ceremony actually takes place every year. And I thought, you know, whoever is going to be repeating this day has to get bored very quickly. It has to be something that he doesn't want to do. And then I started thinking, well, who goes to Groundhog Day? And I thought, well, these local newscasters who go have to cover some goofy little local holiday and have to do it year after year after year, pretend that they like it. That would be perfect; someone who comes from outside, who feels like this town is too small for them, or that they're too big for this town. The fact that it's in the darkest moment of winter, I mean, it just had so many things that seemed to reinforce it as a good idea.

At some point I did what I would call due diligence. It's like, okay, before I commit to this, let me just see if there's anything else out there. And so, I thought February 29th has always fascinated me as a magical date, a leap day. There are other holidays that are well understood, like Christmas, or Phil's birthday, or an anniversary of something that might have meant something to him. I kept going around with all these thoughts and thought, yeah, I haven't done any better than Groundhog Day. It's an unexploited holiday and in my own sort of way of just trying to get myself psyched up that this is a really good idea, this thing I'm about to spend who knows how many months writing, it could become popular and play on television every year, like the Charlie Brown Christmas Special. So, it just struck me as a good idea.

And I thought, okay, so who's the character? Let's see, the groundhog's name is Phil, let's call him Phil. Maybe there will be some chemistry with that idea, which I think happened. It just sort of made sense. He became a weatherman, just sort of by the way, Harold read the script. He never really saw it as a local newscaster because the people who do cover Groundhog Day would be weathermen now that cable weather and everything had started up, the Weather Channel. So, that happened and that was a great idea because who should be able to predict what's going to happen if not a weatherman? So, there was irony. I don't know, I was just sort of sniffing my way into where the most fun would be and where the most dramatic interaction. Groundhog Day.

Michael: I do think, I mean, I think that's a good call for a number of reasons. I was trying to think about that. I think you had mentioned maybe, like, Christmas at one point as a possibility too, but there's so many Christmas movies.

Danny Rubin: That's true and actually, I wrote an adaptation of a Christmas movie that Richard Curtis had done for the BBC. And the first thing I did was I called Richard, and I said, "Does it have to be a Christmas movie?" I've seen a million of them, but personally, I don't have a terrific affinity for all that, especially not the way Richard Curtis does, it's clearly his favorite holiday. So yeah, and he said, "Yeah, do whatever you want." But in terms of making it a Christmas movie, I wasn't leaning into that ever.

Michael: You do have the market on Groundhog Day movies. There's really nothing about Groundhog Day, the holiday itself. Now, we can talk about the repeating day concept, that's a little different. You also mentioned leap day. I was curious if you've seen that 30 Rock where they do the spoof, where they do the leap day movie. Have you seen 30 Rock?

Danny Rubin: I'm not picturing it, so I guess if I haven't seen it or I've mixed it up in my mind with a million other things.

Michael: I can send it to you at some point, but it's kind of funny. It's a part of the show and it's just a very brief commercial that they do for in this episode, leap day is like this big thing. So, there’s a leap day movie and leap day traditions associated with it. It's all created for the show, but the commercial that they do, it actually has Jim Carrey in it and he's playing, it seems like it's very much a kind of a takeoff on Groundhog Day a little bit where it's associated with the day, and he learns a lesson about life and whatever but it's funny. I was just curious if you had ever seen it.

Danny Rubin: I actually don't think I've seen that one.

Michael: All right. I'll send it to you. It's kind of cute.

So, I know that at one point you were writing this with the possibility as it being a TV movie. I don't know how far along in the process— I think you said you maybe sent that version out to an agent and they said they wouldn't be able to sell it. Did you ever have any thoughts on, like, who you would want to be Phil, in that case? Like, did you ever think about it that much? Because you're going to have— Definitely at that point, you have different actors who are TV actors and different actors who are movie actors.

Danny Rubin: I was really hopelessly naive about all that. I never thought about the marketplace. I only thought about what can I write and would I enjoy seeing this? There wasn't anything beyond that. I figured if there was ever a movie that existed that was anything even close to this and it got made, then mine could get made. It didn't occur to me that a movie that got made in early 1960 in London might have nothing supporting it in a Hollywood system.

When I conceived of it as a TV movie, that was simply how could I break it up in a way that would allow me to write it the most easily? I heard that TV movies at the time had, like, seven acts and I thought, well, I had already sort of conceived of the thing as thinking that Phil would go through his life in stages and each stage is sort of like a chapter of his life. I thought, oh, I could fit that into a seven act, each one 15-minute pieces, which made it bite-sized. I could write a 15-minute act in a day and then I could go write the next one and then write the next one. Because my impetus here was my agent had said, "Everybody's already read Silencer. You need to write something else quickly." And my idea was, oh, I've got a lot of momentum on this idea. Let me write this one quickly and get it out there. And by dividing it into seven acts, I thought that was a very clear way for me to set a schedule and to start writing.

But he said, you know, "TV movies are a whole different deal. You can't do this, kind of, super creative stuff." There's, you know, it's like a disease of the week sort of a milieu at the time. So, unless you're writing about somebody who's got leishmaniasis and needs a doctor and they're still setting up the labs, you aren't going to get a TV movie made. But he said, just get rid of the act breaks that I put in and make it a regular movie and he thought he might be able to sell it. So, I did. That took a day, it wasn't hard.

Michael: Okay. Reading the screenplay in the book, that would be, that's the first draft?

Danny Rubin: I suppose first draft, that's not what I sent my agent originally, that's what he sent out. That's the draft that I fixed up and answered having it sit around for a week or two while he was reading it, gave me a chance to look over it, make a few tweaks and smooth it out. So, that was the draft that went out.

Michael: And if I remember correctly, you said something like you spent four or five days doing the actual writing of that draft, but you had planned out, like, maybe several weeks before that what exactly was going to happen? Is that kind of…?

Danny Rubin: It could have been, like, seven weeks. It wasn't like no time, where I was writing little scene sketches and trying to put them in the right order where they would build a reasonable story. The writing of it was in my mind, like, pushing the baby out. I was a full nine months pregnant with all of my ideas and everything, and it was time to just script it. That was the part I did painfully quickly. I've never met that pace since then. I can always tell myself, "Look, give yourself another week. It's not that important and you don't have to drive yourself crazy like that." So, I haven't. But I don't know, maybe that was the best way to have written, really quickly.

Michael: I mean, it seems to have worked out.

Danny Rubin: Yeah, that was a pretty good day.

Michael: So, reading through that script, it seems very similar to what ultimately gets produced. There are, you know, a number of differences. I know you said you were considering it more of a comedy with a romance than a romantic comedy. And I feel like the role of Rita really kind of gets expanded and more integrated into the plot by the time of the final movie. You also began it in the middle, right? Like, that's kind of a famous thing. I feel like I saw interviews that Harold Ramis had done where he said, you know, "Oh, this is the thing we really liked," and he said, "I'm not going to change that," and then that's like the first thing he changed. Are you happy with what ultimately got produced or do you think, is there a part of you that still would have liked that original idea?

Danny Rubin: Oh, I still would have liked that original idea. I don't think that it would have worked quite as well. I think it would have always relegated this to being sort of a culty movie that a lot of people would really like, but not a commercial movie. And at the time I was just, kind of, generically wary that Hollywood was going to take the 10 things that I'd done that were really innovative to me that, you know, Hollywood movies, everyone was complaining even then, you know, everything looks alike and it's starting to be very homogenized and formulaic. And I thought, "Well, it's not that hard to be original. Why don't I do that?" And I thought that would be a good way for me to get attention, which worked, but that once it got chosen to be a studio movie, I was aware that there were going to be pressures to turn it into a studio movie and I didn't know where that was going to come from. You know, Harold Ramis was the one who was interested in the last thing he had done was, I don't know what, Ghostbusters maybe, or Stripes or something, I was afraid that it was going to… that the decisions being made were going to start to shove it into a place of familiarity and mediocrity. So, I was trying to protect things that were original.

So, anytime something really big, like starting in the middle, which was anti-comedy formula for Hollywood, you know, the way you're supposed to do it is "Here's Phil. This is what Phil's like. What’s the worst thing that could happen to Phil? Oh, he could be stuck living the worst day of his life over and over again." That's a very Hollywood way of setting it up. That wasn't the way I was looking at it. So, when a change like that would happen, I was nervous, for instance, the original reason I started in the middle was so I wouldn't have to come up with an explanation for how he got into the time loop. That seemed to me to be a very writerly arbitrary choice. Because I sat down, I wrote down: okay, why is he in the loop? Why is he in the loop? It's a magical clock. It's a wrinkle in time. It's a time machine gone awry. It's a gypsy curse. It's some kind of retribution for something done. I mean, you could just make these up and everyone was a slightly different movie, but it's all the same thing. The problem was that if it starts with a plot-generated idea, then the whole movie has to be about Phil undoing it. How do I, you know, like in Big, how do I find the machine that was here so I can undo the magic? And I didn't want it to be about the plot because to me, what was most interesting was just the situation. The fact that Phil was stuck in this day made him exactly like us. We don't know how we got here, and we have to figure out every day what we're supposed to do, not how we're going to get out of it.

So, anything like not starting in the middle meant, okay, that means we have to go through whatever happened and how are we going to deal with that? And that's exactly what happened. All of a sudden, the studio said, "Okay, we need a gypsy curse scene." And I said, I really, "Please, please, Harold, don't make me write a gypsy curse scene." [laughs] And he said, "Don't worry. We'll shoot it, we'll cut it out of the editing room, it'll never make it into the movie, but it'll make the studio happy." And I understood Harold, I mean, he was a great guy, and he was very savvy about the politics of Hollywood in ways that I was completely unsavvy. And yet I was not ready to just capitulate. So, what he got out of me a lot of the time was, "Yeah, you could do that, but you know, how about if we just did this?" [laughs] So, there was a little bit of, if he wanted to honor what I was doing and yet he had to move forward, and I didn't have a clear path. So, that was where a lot of these, sort of, Hollywood decisions started getting made.

Michael: I did see, you at least wrote one scene, and I think it was something like Phil cut someone in line at a concert, I think that was what was in your book. I don't know if there were other ones. I think you said none of them actually ever got filmed though, right? Like, none of those ideas?

Danny Rubin: I'm pretty sure they didn't. There was stuff that went on that I didn't know about until later, so it could have happened, but I don't think so. And the story I heard without any real knowledge was that Heidi Fleiss, the "Hollywood Madam," had her book discovered or published or whatever, and there were a lot of people in Hollywood who were scrambling to save their families. One of them was the head of production at Columbia Pictures. And so, during a very critical period of time where the studio could have been riding rough shot over us, they weren't paying attention.

Michael: Oh, really?

Danny Rubin: It was during in this little creative vacuum that Harold went ahead and made the movie the way he wanted to.

Michael: Oh, interesting. So, a little less oversight maybe?

Danny Rubin: Hearing over and over again, almost every movie that comes out of Hollywood that's amazingly creative and different, it's because somebody wasn't paying attention. [laughs] I know that Harold wrote some versions of the gypsy curse also, or it was a wronged girlfriend who had some kind of supernatural powers. I hated it from the beginning, and it really hurt me because I was watching what looked like a very promising career for me getting launched and then destroyed all at once. [laughs] But somehow the tensions between my pushing for a more classy and classic kind of movie with Harold's pragmatism and, you know, smarts and sense of humor and everything else and spirituality, those dynamics built the movie that you see.

So, I found it the first time I saw it a little bit disorienting because there's the movie that's in your head— Every writer does this, there's the movie that's in your head and then you see the movie that was made and it's very similar and yet just different enough to be, like, disconcerting. But over a very short period of time, I saw how the audiences were responding and I was like, "Yep, they get it." So, I like it.

Michael: And that's the first part of the interview. As I mentioned earlier, part two will be released on Groundhog Day. Music for this show was written by the Hibernating Breakmaster Cylinder. Show artwork is by Tom Mike Hill. Transcripts are provided by Aveline Malek at TheWordary.com. If you want to learn more about Groundhog Day, visit countdowntogroundhogday.com. We've got a growing list of Groundhog Day celebrations taking place over the next few days. If you don't have plans, check it out. Any feedback or voice messages about the show can be sent to podcast@countdowntogroundhogday.com. Thanks for listening, talk to you next time!

--------

Transcribed by Aveline Malek at TheWordary.com